PHILIPPE FOREST

Hi! My name is Philippe, and this is my portfolio. I'm interested in neuroscience, music, and recent advances in deep learning. I'm curious, creative, and I try to learn new stuff everyday !

MOVIE CREDIT EXTRACTOR

Introduction

The French National Library (BnF) was founded in 1537 by François 1er. It's mission is to collect, preserve, enrich and communicate the national documentary heritage. On top of its massive collection of books, it also contains 390 000 video documents, many of which are in the process of being numerized in order to make them accessible by the public on Gallica. However, the process of documenting every movie with the appropriate metadata is very time-consuming, and performed by the same specialized personnel in charge of the numerization, who (surprisingly enough) told me that they do not appreciate spending their time filling out charts with the name of the second assistant cameraman. As part as my 4 month internship, I was tasked by the library to produce a proof of concept algorithm capable of :

1) Automatically detecting the beginning and the end of the credits in a movie

2) Performing OCR to extract all the relevant information

3) Structure said information in a standardized way, so that it would be ready for querying on Gallica.

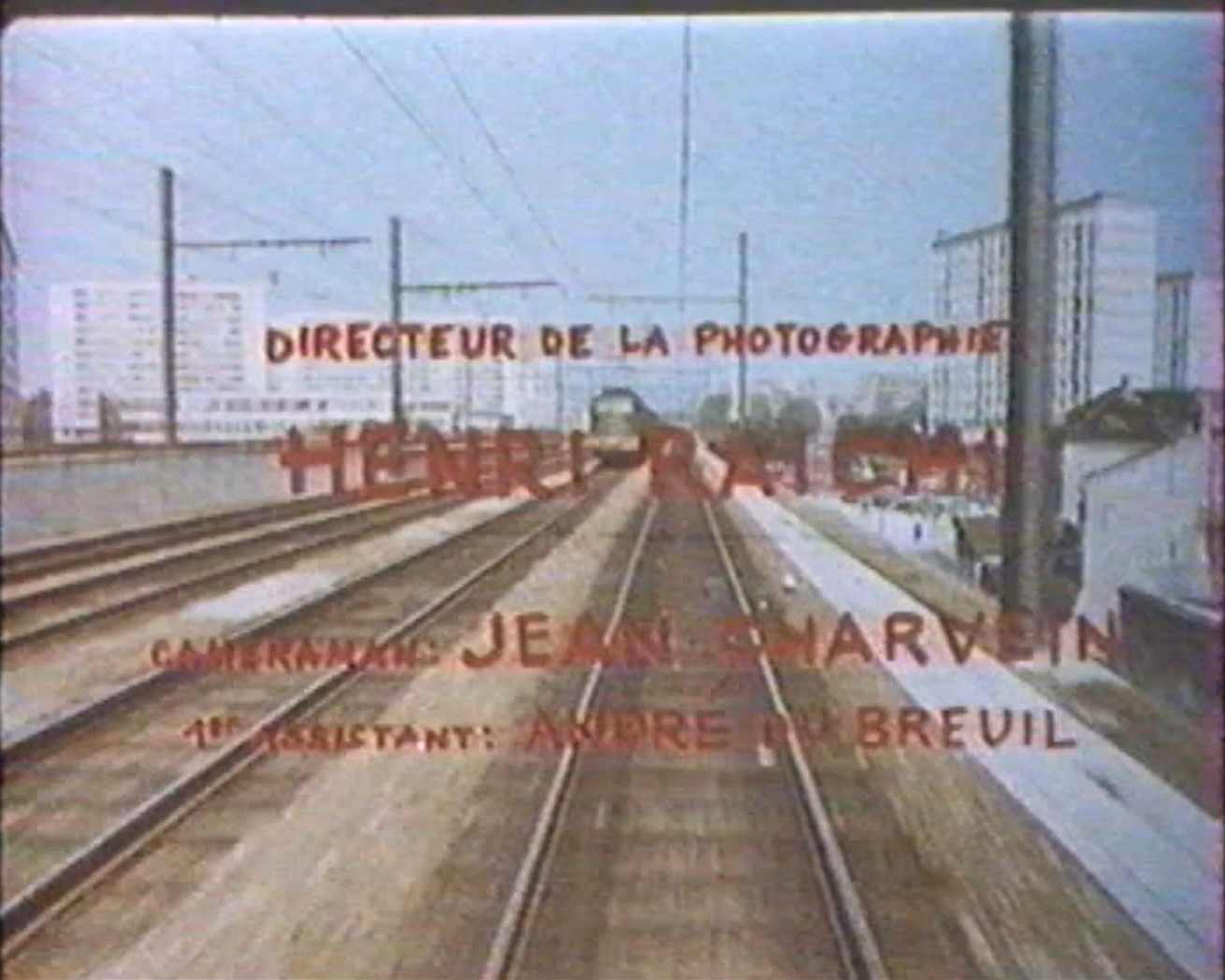

Credit scene segmentation

Segmenting the movie credits was the first part of the job. My first idea was to first build a model capable of detecting whether or not a specific frame was part of a credit scene or not. Then, I would just have to select a frame from the movie every so and so, and decide that the credits have begun to roll when a few consecutive frames were identified as belonging to a credit scene. After a little bit of research, I found pre-trained models that could fullfill this purpose, such as this one or that one. After a few test on actual videos from the BnF collection, I noticed that such models were pretty efficient to detect the credit sequences when they looked like black screen with white next appearing on it, but failed completely whenever the credit scene was anything else. As it turns out, many of the BnF's movie have ending sequences that completely differs from this stereotypical design. See the following picture for an idea of what I had to deal with :

The next step was to retrain/finetune an existing model using more diverse and colorful credit sequences, so I spent some time building a collection of screenshots from the most original pieces I could find in the BnF database. The new model performed slightly better on colorful samples, but was still overall pretty unreliable. Inspired by a different idea presented on this project, I decided to switch strategies : instead of identifying whole frames as being either "credit" or "non credit", it could be interesting to instead simply detect the presence of text on the screen, regardless of everything else. After a little empirical experimentation, I added a moving average of 10 seconds in order to rule out the occasional shots mid-movie that showed a sign on the road, or an eventual text interlude (think old Chaplin movie), and bingo! Our new method correctly identified both beginning and ending credits with more than 95% accuracy! One last addition consisted in detecting if the movie had subtitles or not, and ignoring them if that was the case. It was now time to actually extract the information from the movie.

Optical Character Recognition

This part of the process was pretty straightforward : I experimented with many different OCR algorithms available, some open source and other not, among which : EasyOCR, ABBY Finereader, pyTesseract, Google OCR and CRAFT (which I also used for text detection in the previous part). The absolute unmatched winner emerged as Google OCR, with results that quite honestly almost equaled human performance. Given the difficulty posed by some of the images (see screenshot above if you don't believe me), we decided to continue with this solution. I performed a brief estimation of the pricing and estimated that we could process the entirety of the video collection for less than a hundred euros. It was now time for the final step, the data processing, formatting and structuring.

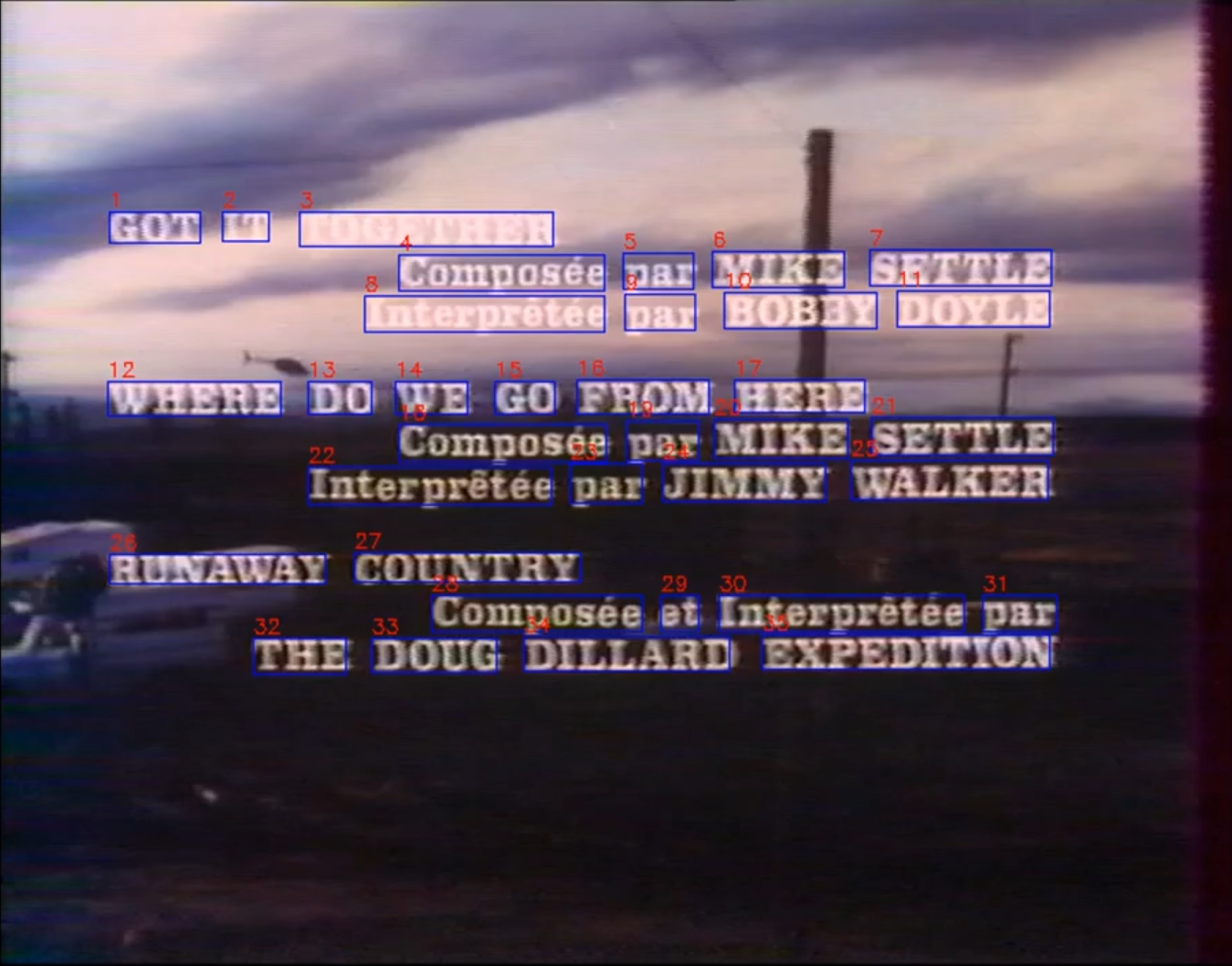

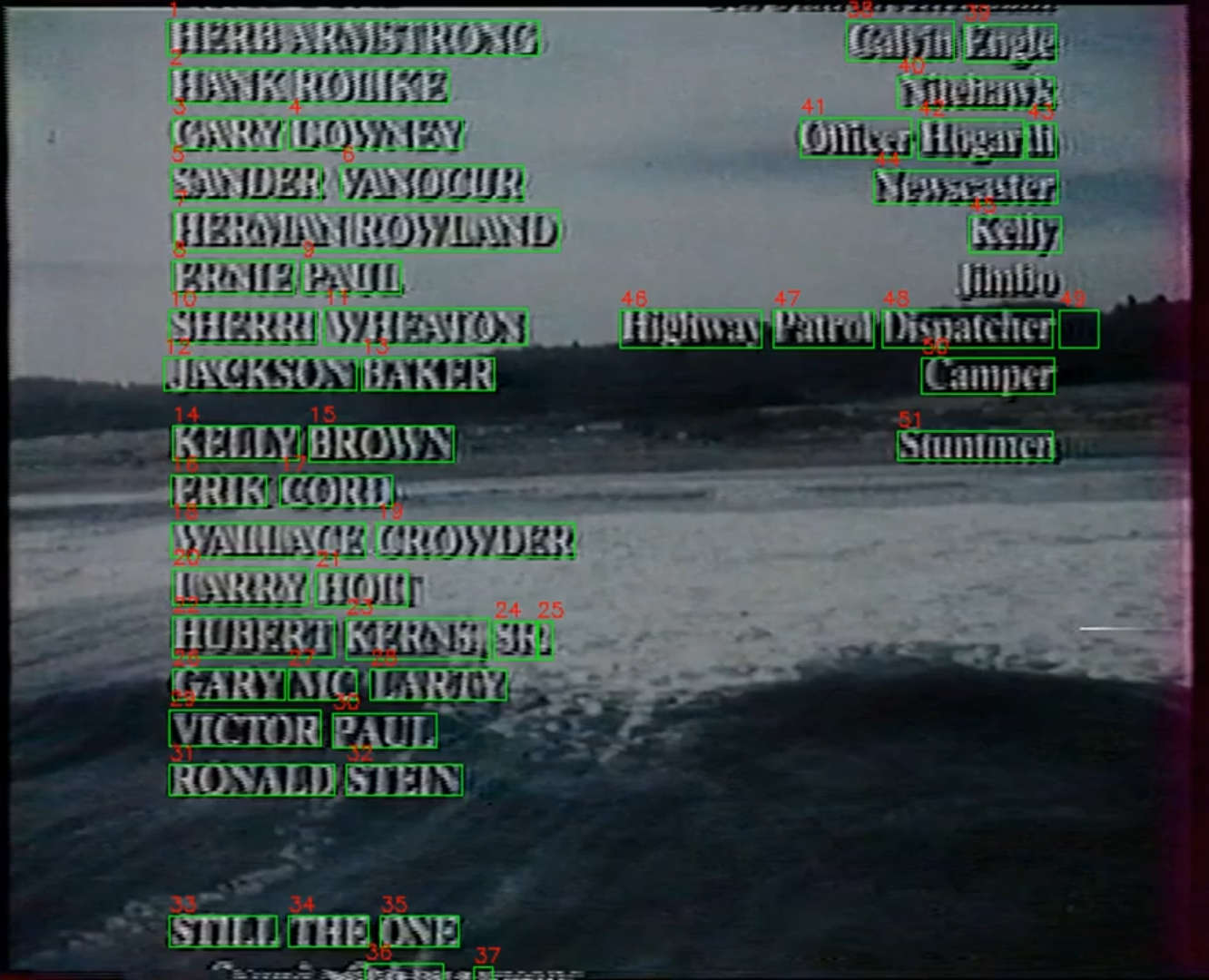

Data structuring

Though it might not seem that way at first, this part of the process is actually by far the hardest. Think about it : some credits sequences roll from bottom to top, some other just jump from screen to screen, some have the name displayed before the corresponding role and some have the opposite. Some have one column, two column, or even three columns of text. A lot of time, the format of the display changes during the same credit sequence! Let's see two examples from the BnF to try to identify all the things our algorithms should do correctly :

Ideally, to perform as good as a human reader, our algorithm should be able to understand that on the first image, the three lines in capital letters correspond to song titles, but the other words in capital correspond to people's name, and the other test on the left correspond to these people's fonctions relative to the aforementioned song. On the second image, however, the actor's name are written on the left, and their corresponding roles are written on a different column on the other side of the screen. Based only on these two examples, you can imagine that it is impossible to treat every case one by one. To top it off, some movies will adopt stricly opposite conventions : in one example I found, a movie had it's actors name written in uppercase on the left and the corresponding roles in lowercase on the right. In other movie, the roles were written in uppercase on the left and the corresponding roles were in lowercase on the right. When the roles themselves are written as a name, even a human reader could get confused!

Conclusion

At the end of my internship, I still hadn't found a complete and precise way to parse accurately the information in most of the credits, and to be honest, I doubt that such a solution exists without advanced machine learning techniques. However, here is what I found :

- The first step is to discriminate between rolling credits and static credits, because an algorithm made for the later will probably generate repetitions if it is applied to the former, and vice versa. This is not too hard to do however, for instance, by tracking the position of words on the screen over one second and see if there is some drift. If that is the case, we can take a new screenshot of the content of the screen everytime the bottom-most word of the previous screenshot has disappeared.

- Once the relevant screenshots are acquired, it is essential to begin with a segmentation of both the lines and the columns, to uncover the structure of the

information displayed.

- Once this is done, semantic analysis can be performed. We are looking for words such as "director", "actor", "cameraman" etc. It is often very useful to keep track of uppercase and lowercase as it often serves a semantic purpose, just like the line and column segmentation. It is also good to automatically correct words that are obviously misread such as "direptor".

- The semantic and structural information collected on one screen should not be used to interpret the other screens, as the display changes from one screen to the other in most credits. Each screen should be treated in it's own right.

- Finally, we can begin to pair the names with the roles, based on all of the information collected previously. Ideally, our data should eventually look like a dictionary where the keys are the roles and the values are all the associated names. However, it is always a good idea to keep all the identified roles in a separated list, and all the names in another list as well.

I would like to thank Sebastien Cretin, my internship director, as well as Laurent Duplouy, the head of the project, and the rest of the department at the BnF for this wonderful and enriching professional opportunity.