PHILIPPE FOREST

Hi! My name is Philippe, and this is my portfolio. I'm interested in neuroscience, music, and recent advances in deep learning. I'm curious, creative, and I try to learn new stuff everyday !

WATERMARKING OF DEEP CNN

Introduction

In order to protect the intellectual property of fully trained models, which often take time, money and effort to develop, neural network watermarking is receiving increasing attention over the last several years. Lots of factors need to be taken into account when designing a watermarking scheme : among them is the robustness criterion, which stipulates that the watermark should be resistant to retraining of the model, pruning of the model, and overwriting (putting another watermark on the same model should not erase the previous one). Moreover, the watermarking scheme should not affect the model's accuracy.

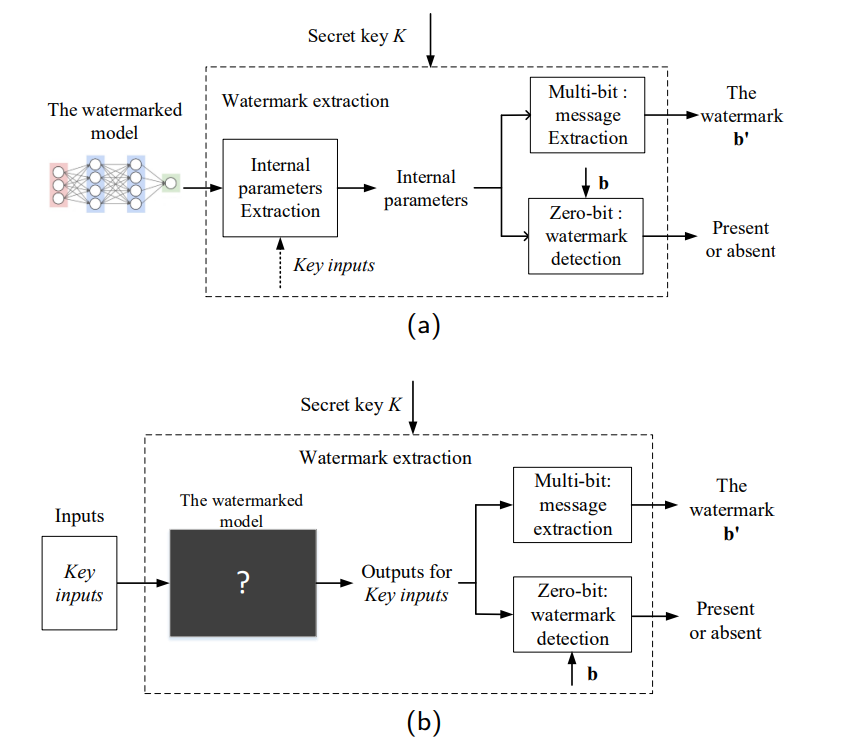

The first idea and implementation of such an algorithm was proposed by Uchida et al. in 2017. The idea was to embed a binary message inside of the weight repartition of a deep convolutional neural network. The message is embedded during the training phase and can be recovered by anyone having access to the weight distribution, if he possesses the secret key that was used during the embedding process. It may not seem ideal that one need to have access to the weights in order to recover the message (what is called a "white-box approach", but it has been showed that the alternative (i.e recover the watermark only by querying the model) necessarily impact the model's accuracy. Here, I will implement Uchida's algorithm, highlight its strenghts and weaknesses on a model trained on the CIFAR 10 and MNIST datasets, then implement a more recent and robust algorithm, RIGA, that takes inspiration from GANs to make up for the shortcomings of Uchida. The notebook with all the codes is available here

Uchida's algorithm

Uchida's method works as follows : once we have our n-bit binary message to embed, we select the convolutional layer of the CNN that we would like to watermark. Then, we generate a random matrix whose elements are drawn from the normal centered distribution. This matrix will be our secret key used to embed the secret message during the training process, and will also be used in order to recover the message. To do so, Uchida's amazing idea is to add one more term to the loss function, that will act like a regularizer (think of a weight decay term, but instead of penalizing big weights, it penalizes weights distributions that don't "match" the secret message we want to embed). Of course, by now, the burning question is : how do we force a weight distribution to "match" a secret message? and what role does the secret key has to play in this? The answer is pretty simple : n linear combinations combining both the weight distribution and the secret key components are generated. Each of these linear combinations is supposed to add up to one of the message bit at the end of the training process. Therefore, the neural network is incited to modify its weights such that :

1) It acquires a good accuracy (that's the role of the first part of the loss function)

2) The weights involved in each of the n linear combinations are set to values such that the combinations produce all of the message bits, in a given order.

In practice, the way we achieve this is through a cross-entropy loss function, since this problem is analoguous to a binary classification, with the labels being either 0 or 1 (the bits of the message)

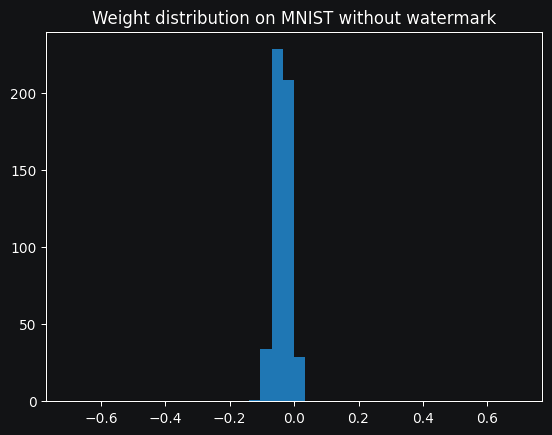

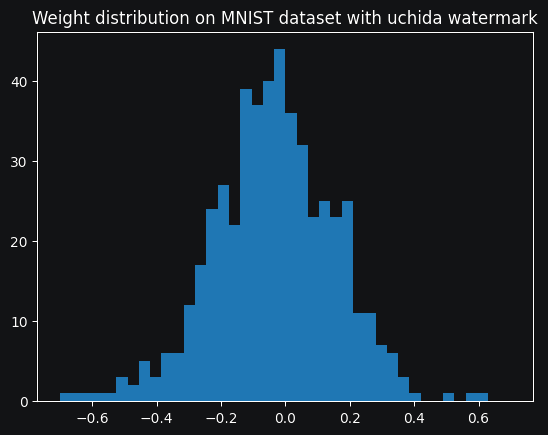

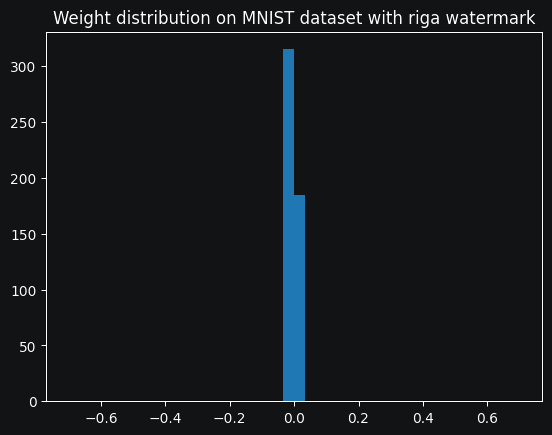

The implementation of this algorithm is pretty straightworfard, and can be found in the notebook. I implemented it on the CIFAR-10 and MNIST datasets, using a slighty improved version of LeNet. I noticed a 2% decrease in accuracy on the CIFAR dataset when applying the watermarking, but I was able to successfully embed and retreive the message with a 100% recovery rate. However, upon looking at the weight distribution of the embedded layer, it is obvious that the repartition had been tampered with :

This breaks the principle of security, which states that the matermark should be inpossible to detect. It is one of the biggest flaws with Uchida's algorithm. Now let's try to implement RIGA in order to see if it fares better .

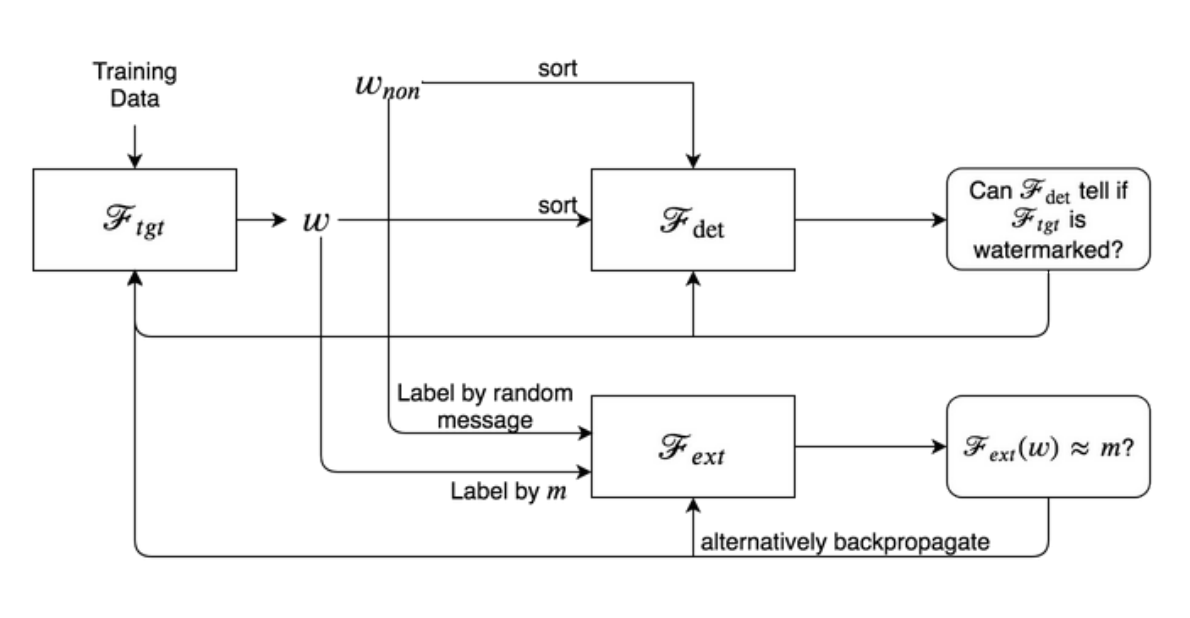

RIGA algorithm

RIGA adresses the issue of weighth distribution by cleverly drawing inspiration from GANs. To simplify a little bit, RIGA ditches the linear combinations that we mentioned earlier, and replaces them with a multi-layer perceptron whose job is to take as inputs the current model's weight, and map them to the appropriate message values. This update is not very surprising since, as we mentioned, the initial problem was identical to a classification task using cross-entropy. Moreover, by replacing the rigid linear combinations with a flexible neural network, we can now embed not only binary messages, but pretty much anything we want! However, the real kicker added by RIGA is the introduction of yet another neural network, whose job is to analyse the current model's weights, and predict whether or not these weights have been tampered with. The model in charge of mapping the weights to the message then receives a penality if the weight has been deemed suspicious by the second neural network. This is of course very similar to the way GANs work, with a generator trying to produce an element belonging to a specific distribution (In this case, the distribution of all possible non-watermarked weights), and a discriminator tasked to identify the outliers. To make this work, we first need to generate a bunch of non-watermarked weights so our discriminator can have a reference to decide whether or not a new weight distribution is watermarked or not. The following diagram is a brief summary of the whole scheme, where wnon stands for non-watermarked weights, m is the message to embed and Ftgt is the target model for our watermark.

RIGA and Uchida comparison

Not only is this method supposed to hide the watermark seemlessly, but it is also said in the original article that it is robust to pruning and overwriting. Let's try it out! Once again, the code is available in the notebook.

This algorithm implementation was definitely harder than the previous one, mainly due to the multiple neural networks interacting with each other and the three chained backpropagations required to update the weights. First, let's look at the weight distribution in the embedded layer :

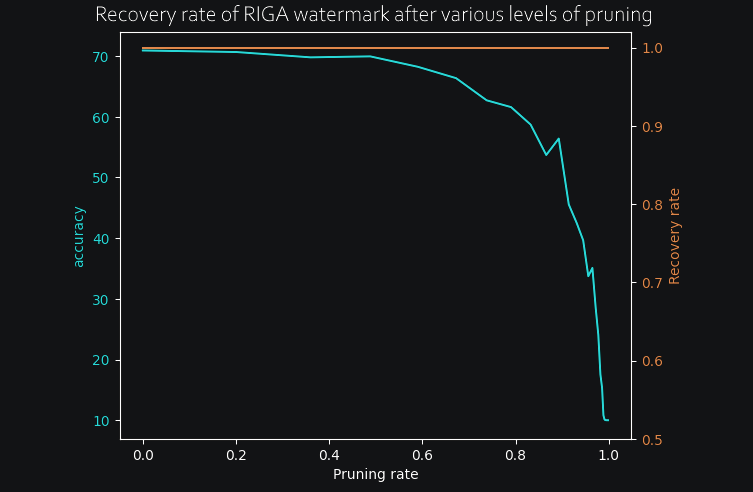

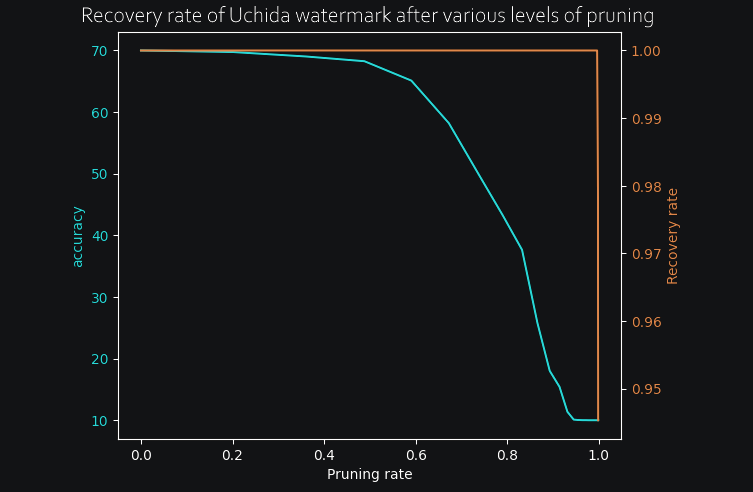

Much better! Once the training was complete, I pruned progressively more and more of the network and kept track of both the accuracy and the watermark recovery rate at each step. Here are the results for both Uchida and RIGA :

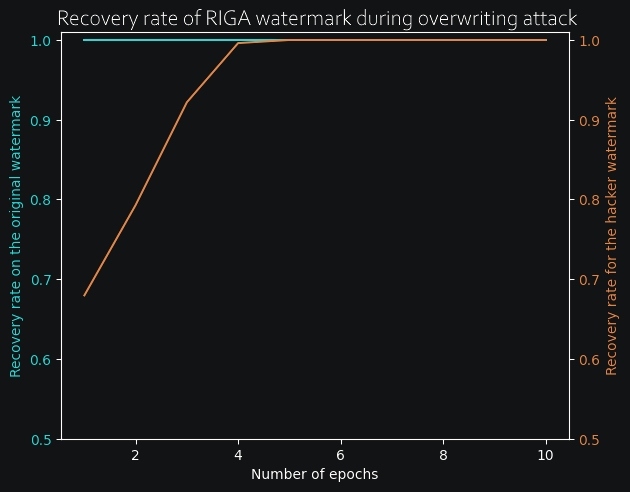

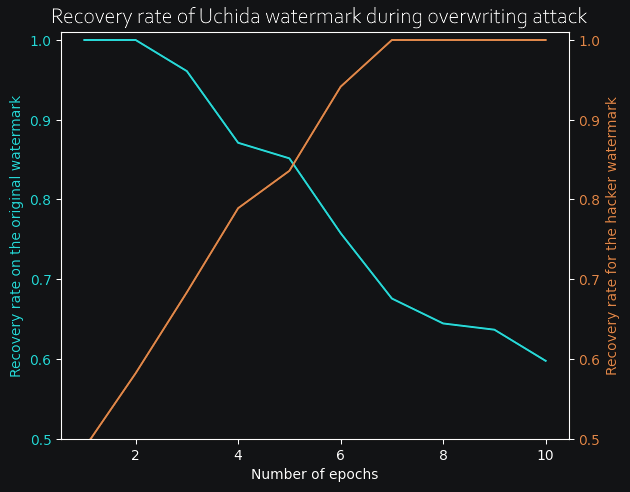

In both cases, the watermark only begins to degrade long after the accuracy is completely destroyed, so we can safely say that both methods are resistant to pruning, at least on this small test case. Now, for the really interesting part, I wanted to see how both models would react to an overwriting attack. To do so, I have progressively retrained the models by adding a new watermark at the same time, and kept track of both the old watermark recovery rate (in blue) and the new watermark recovery rate as it is slowly added to the model. (in orange). Here are the results for both RIGA and Uchida methods :

Conclusion

The difference here is obvious : with Uchida's algorithm, the more epochs we retrain with a new watermark, the more the previous watermark begins to degrade. However, with RIGA, the old matermark remains entirely recoverable even after a new watermark has been added to the weights. Therefore, RIGA adds a lot more robustness as well as being virtually impossible to detect from weight distribution alone.

Other algorithms I have not covered are designed so that the watermark can be introduced in the model during the process of fine-tuning, or even during distillation. The field of neural network watermarking is still relatively new and expanding, so there is no doubt that more of these clever algorithms will pop up in the years to come!